SPRING 2021, THE EVIDENCE FORUM, WHITE PAPER

Anne Skalicky, MPH Research Scientist Patient-Centered Research Evidera, a PPD business |  Asha Hareendran, PhD Senior Research Leader Patient-Centered Research Evidera, a PPD business |

Introduction

Decentralized trials provide new opportunities to achieve more diverse geographic and socioeconomic patient participation in clinical trials.1 Proactively assessing study design and recruitment approaches to improve access and diversity has become an essential aspect of decentralized trials.2

In the past year, recruitment for COVID-19 clinical trials faced unprecedented challenges.3 There was a need to fast-track trials for testing treatments for people at high-risk for disease complications. COVID-19 treatment trials that favored a decentralized approach, however, were faced with additional challenges. Potential participants lacked a familiarity and understanding of the clinical trial testing and drug development processes, which exacerbated these challenges.

Early engagement with potential study participants at the start of clinical trials presents an opportunity to explore patients’ expectations, experiences, and perspectives; examine recruitment approaches and materials used to support recruitment; and explore what resonates with target subgroups.4 This article will discuss a case study which gathered patient insights using qualitative methods to provide a more in-depth and nuanced understanding beyond the restrictions of traditional survey methods.5

Case Study Overview

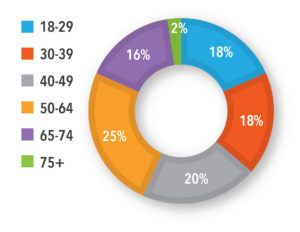

Population: A sample of 100 adults who tested positive for COVID-19 from April 2020 to October 2020, experienced symptoms, and sought medical consultation or treatment. The sample included specific age and race/ethnicity targets. Adults considered high risk for COVID-19 progression (≥55 years of age and/or with a comorbid condition) made up about 50% of the sample.

Challenge: To address recruitment challenges related to COVID-19 treatment trials aimed at reducing symptom duration or disease progression.

Approach: Focus groups and interviews. Ahead of the interview, a structured questionnaire asked participants to characterize their experience with the disease (symptoms, duration, severity), treatment information, medical consultation, and any expectations and/or experience participating in a clinical trial. A semi-structured interview guide was used to support the qualitative research; trial outreach materials were also discussed.

Key Findings: Most of the participants were female (64%), from the United States (89%) or the United Kingdom (11%), at high-risk for progression of COVID-19 (55%), with diverse ages and ethnicities (See Figures 1 and 2). Symptoms ranged from mild to moderate, with fatigue, muscle aches, headache, and fever resolving after two weeks. Several individuals in the high-risk group reported severe symptoms and complications that required hospitalization. The groups discussed the need to understand a COVID-19 patients’ journey from testing to diagnosis and treatment, the path to wellness, and the potential touchpoints and opportunities for recruitment. Ensuring the right stakeholder to support recruitment, especially one that potential study participants could trust, would be important, as was the patient’s motivation to test for COVID-19, the timing of the test, and touchpoints with healthcare professionals and testing centers.

Finding the Right Avenues for Recruitment

“It wasn’t like I had it and it was over, you start feeling good after a week – and then bam, it hits you again. That happens for about 2-3 weeks: you feel great, and then all a sudden I couldn’t do anything.”

– US029, high-risk group, Age 50-64, male, White American

Pathways for obtaining a COVID-19 test were similar across age groups and ethnicities in the United Kingdom and United States (US). Overall, most participants (86%) reported getting tested only after developing symptoms. A small subset, 26% of US Spanish speakers, reported getting tested before developing symptoms, mainly due to known exposure or job requirements.

Participants said they found COVID-19 testing sites via local public health websites or from friends and family. A large proportion (43%-58%) consulted a healthcare professional to identify a testing site location or testing site appointment system. The high-risk participants were more likely to seek medical consultation before testing positive for COVID-19 compared to those with a lower risk. Everyone agreed that their medical doctor, healthcare team, or other highly regarded public health or medical authority, such as a local hospital, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, etc., would be a trusted source for information about COVID-19 treatment trials.

Some participants said receiving information about COVID-19 treatment trials at a testing site might not be ideal since people waiting for a COVID-19 test may be apprehensive and unreceptive to trial advertisements or flyers. Several pointed out that since they knew where to go to get tested, they could have been made aware of treatment trials if they had been advertised in the same way. They also noted that people who seek testing before they develop symptoms (i.e., in the case of known exposure) may be more receptive to learning about treatment trial opportunities. The high-risk group also thought people in a similar demographic may be easier to target since they receive regular medical care and are likely aware of the potential risk for long-term symptoms and/or complications. The recommended touchpoints for recruitment to COVID-19 treatment clinical trials were healthcare providers, COVID-19 testing sites, local public health websites, and contact tracers.

“When someone is positive and sick, the timing does not allow to find out about a treatment trial and enroll. It would be important to get the word out before people get sick.”

– US-038, Low-risk group, Age 50-64, female, White American

Drivers for Participation in Clinical Trials

“Since I had symptoms for 1-2 days, I would only participate if I had more symptoms, knowing there is a potential benefit to participating.”

– US-026, High-risk group, Age 50-64, male, Hispanic American or Latino

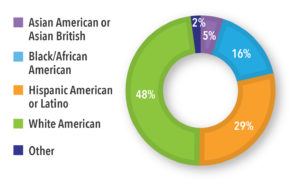

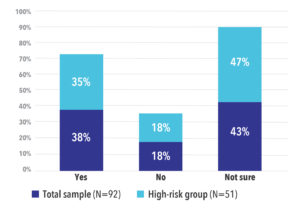

Overall, 38% of all study participants indicated they would be willing to participate in a COVID-19 treatment trial while 43% said they were not sure. In the high-risk group, 35% said they would be willing to participate and 47% said they were not sure. Only 18% of both groups said they would not participate in a trial (See Figure 3).

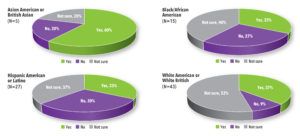

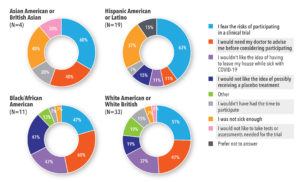

Most Asian American and Asian British participants said they would consider participating in COVID-19 treatment trials. White American, White British, Black/African Americans and Hispanic Americans/Latinos were less sure (See Figure 4).

Figure 3. Participants Who Would Consider Participating in a COVID-19 Treatment Trial by Risk Group

Addressing Barriers to Participation in COVID-19 Treatment Trials

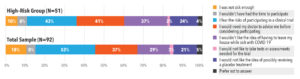

When asked why they were hesitant or did not want to participate in a clinical treatment trial, many participants said they were afraid of an unknown treatment and unsure whether the risk of complications was greater than the risk of a new treatment. Ideally, they wanted a doctor to advise them whether to participate. In the high-risk group, participants said they would be worried about leaving their house while sick with COVID-19 to fulfill clinical trial requirements (See Figure 5).

Similar barriers were discussed across race/ethnicity groups. The top four barriers were fear of the risks of participation, not thinking they were sick enough, wanting a doctor to advise them, and not wanting to leave the house while sick with COVID-19 (See Figure 6).

“Time would be an obstacle for me. I would be motivated if it didn’t take a lot of time.”

– SP03, Low-risk group, Age 65-74, female, Hispanic American or Latino

Considerations for Enhancing Diversity of Clinical Trial Sample

“I have diabetes. I would participate if I knew side effects would be minimal, and if someone can advise me. I like that you can participate in the trial at home.”

– SP024, High-risk group, Age 40-49, female, Hispanic American or Latino

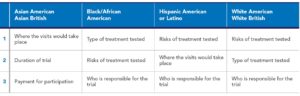

Overall, participants noted that they would like more information before deciding whether to participate in a treatment trial. Across race/ethnicity groups, what information participants wanted to know before participating in a treatment trial varied (See Table 1). African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and White Americans wanted to understand the risks of the treatment being tested, as well as who was sponsoring or was responsible for the treatment trial. For Asian Americans and Hispanic Americans, knowing where the trial would take place was most important.

Table 1. Top 3 Things Potential Participants Want to Know About COVID-19 Treatment Trials: Information to Include in Recruitment Materials

Participants had many opinions about the COVID-19 clinical trial study flyer used to advertise recruitment and made suggestions for what other information should be included on the flyer or made available on a recruitment website. Practical information about what the trial entails also factored into the decision-making process:

- Is this an existing medication or a new medication?

- What procedures are involved?

- Will there be a medical professional available if I have questions?

- How will I be monitored?

- How long will the trial last and what responsibilities do I have as a participant?

- Can treatment and/or assessment be done at home?

- Who is the study sponsor?

- What are the potential benefits and risks of participating?

- Are study participants compensated? If travel is required, will travel expenses be reimbursed?

Name recognition is also important, as is trust in the company running the trial. Trial recruitment materials should consider using inclusive pictures or graphics depicting broad age, gender, and ethnicity ranges. The slogan for the study should also be a broad message that draws people in, and should have an option for a website, text/SMS, or QR code for people to access more information or have options to speak to a healthcare professional directly. Many talked about the value of focused messaging to appeal to humanity’s altruistic nature and desire to help others during the pandemic.

“It [feels like] kind of the right thing to do, but I’d need to be pretty majorly reassured [on what will need to do].”

– UK05, Low-risk group, Age 40-49, male, White British

“I would be motivated to participate if I can help someone else and keep them from going through what I did.”

– US068, High-risk group, Age 75+, female, Black/African American

Lessons Learned from Early Engagements

Through early engagement efforts using in-depth qualitative focus groups and interviews it is possible to understand a patient’s experience, the touchpoints patients might have with the healthcare system, the potential barriers and motivators for clinical trial participation, and messaging that could enhance recruitment.

In the case study presented, a diverse group of patients with previous experience with COVID-19 explored ways to enhance diversity in clinical trials. They discussed patient-preferred touchpoints where they receive information about treatment trials, trusted sources for receiving information, and preferred clinical trial messaging. This patient engagement effort resulted in informing recruitment strategies and ensured that outreach materials for the COVID-19 clinical treatment trials contained inclusive messaging, appealing images, and accessible information.

References

- Milken Institute. Krofah E, Schneeman K. Lessons Learned From COVID-19: Are There Silver Linings for Biomedical Innovation? Available at: https://milkeninstitute.org/reports/biomedical-innovation-covid-lessons. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations — Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Guidance for Industry. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/enhancing-diversity-clinical-trial-populations-eligibility-criteria-enrollment-practices-and-trial. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Relias Media. COVID-19 Misinformation Affects Everyone in Research Community. Available at: https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/146927-covid-19-misinformation-affects-everyone-in-research-community. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Patrick-Lake B. Patient Engagement in Clinical Trials: The Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative’s Leadership from Theory to Practical Implementation. Clin Trials. 2018 Feb;15(1_suppl):19-22. doi: 10.1177/1740774518755055.

- Getz K, Sethuraman V, Rine J et al. Assessing Patient Participation Burden Based on Protocol Design Characteristics. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2020 May;54(3):598-604. doi: 10.1007/s43441-019-00092-4. Epub 2020 Jan 6.